|

|

Buoyant Economies Growth of Debt and Loss of Income in America |

||

|

|

Twin problems The American

financial system has two major problems. Together, they are like an

iceberg. One is is US debt which is large and

obvious. The other is the loss of income and this is enormous, costing

at least 10 times the first. Although the income problem has been

present for many years, it has never been perceived as urgent or critical;

and so it has been ignored, and is effectively unseen. The obvious problem

has been the growth of domestic and foreign debt. Over the 25 years to

2011, debts to American banks have grown at an average rate of $0.8 billion

per day. The rate of growth has been increasing. From 2000 to

2011, it had been averaging $1.6 billion per day. On the other hand,

the unseen income problem is currently costing the American economy about $23

billion per day over that period, and continues to grow. This income problem

has caused the demise of manufacturing and other import competing industries

and the reduction of the rate of economic growth. The loss of income is

a side-effect of policies that President Richard Nixon implemented in 1973 to

treat symptoms of the debt problem, which at that time was manifest as a fall

in foreign reserves of the banking system. The economic consequences of

Nixon's policies are more apparent when we consider some of the factors they

have affected. For example, as shown in Figure 1, by 2011 average real

wages for production workers in America is lower than they were in 1973.

Real wages for American workers would be about 80 per cent higher in 2011 if

it were not for the highly promoted yet misguided policies that President

Nixon put into effect.

Real wages had been

rising up to 1973. Suddenly, the situation changed and real wages fell dramatically.

It is clear that something changed in 1973 that significantly changed the way

the economy behaved, putting the USA on a path of self destruction. President Nixon's

policies treated the symptoms of America’s economic problems; not the cause.

So today, America:

·

suffers the side effects of the policies that President Nixon implemented in

1973[3]. If America is to

achieve a healthy and sustainable economy, it needs to address these two

basic problems. America shares these problems with many western economies

that were prosperous up until the end of the 1960’s but which are now deeply

in debt, and have high rates of unemployment. These problems have

spread because President Nixon’s policies have been widely promoted around

the World, particularly by the International Monetary Fund. These

policies are now a normal part of the modern Western economic framework.

Therefore, to even question them opens one to ridicule.

Nonetheless, those policies are like the king’s new clothes; they are highly

revered but lack substance. Background Before proceeding to

explain the American economic situation more specifically, it is useful to

consider the experience of an extremely small and much simpler economy.

Although small, it is a useful example because it is a real model

and its economy behaves in a similar manner to larger economies. It is

more revealing than theoretical models that reflect the preconceived theories

of their proponents. In August 1980, I

joined the Ministry of Finance of the Kingdom of Tonga as the economist.

At that time, the Ministry of Finance was responsible for both fiscal

and monetary policy. Tonga had

established its first bank in 1974. Before then, the post office

provided some banking services. However, it did not lend money.

Hence, before 1974, all domestic currency was created through the increase of

foreign reserves. That is, when people brought foreign currency into

the country, it was converted to Tongan currency and the government held the

foreign funds in reserve until the people (particularly wholesale importers)

wanted to convert their money back into foreign currency. When the Bank of

Tonga was established, it started to create additional money through the

growth of bank lending. That money did not increase foreign

reserves. Yet it enabled people to spend, just like money that came

from foreign sources. Therefore, when the money from bank credit was

spent on imports, those addition imports financed by the growth of bank

credit needed to be paid for in foreign currency. Those additional

foreign payments depleted the governments foreign

reserves. Early in 1981, the

Ministry of Finance became aware that Tonga’s foreign reserves were being

depleted. The Ministry eventually traced the cause of the falling

reserves to the growth of bank lending. It found that when bank lending

increased, foreign reserves decreased. When bank lending declined,

foreign reserves increased.

The Treasury

realised that if Tonga was to maintain its foreign reserves and the security

of its currency, it must manage the growth of bank credit.

Consequently, the Secretary of Finance wrote to the Bank of Tonga advising it

that if foreign reserves were greater than the equivalent of six months

imports, the bank could lend without restraint. However, if foreign

reserves were to fall below that level, the bank was to start restricting its

lending. If foreign reserves were to fall to 3 months imports, it could

maintain existing lending levels (lend what was repaid). If foreign

reserves were to fall to 2 months imports, it was to cease lending. In March 1982,

Hurricane Isaac devastated most of Tonga’s export industries. Yet

Tonga did not experience any balance of payments problems. The Bank of

Tonga managed its lending according to the availability of foreign funds[4]. In 1985, Tonga

joined the IMF. In its first Article IV report, the IMF commended the

government for the success of its lending policies. Although the

original policy is no longer binding, Tonga continues to mange the growth of

bank credit according to the level of its foreign reserves. These

foreign reserves are currently in excess of the equivalent of nine months imports[5]. In such a small

economy as Tonga, it is obvious that any growth in bank lending would

increase spending and lead to a rise in imports that would deplete foreign

reserves. Tonga’s policy response was to manage the growth of bank

lending according to its available level of national savings[6], or

foreign reserves. The point to

acknowledge from this example is that bank lending creates additional money

and it is this additional money that generates the demand for additional

imports. Money that is earned

enables the income earner to buy the equivalent of what they have

produced. In that way, money constrains expenditure to income, or

production. But the additional money from banks (created when banks

lend more than has been repaid in loan repayments) enables people and

businesses to buy more than has been produced. That additional spending

causes current account deficits. American

response

Figure 2: The

rate of growth of US bank credit, January 1948 to March 1973 When America’s

foreign reserves problems were seen to persist, it appears that Milton

Friedman and the Federal Reserve convinced President Nixon that the most

appropriate approach to resolving the problem of the declining foreign

reserves and the speculation on the value of the dollar was to float the US

dollar. Floating the dollar

was part of Milton Friedman's theory for eliminating economic cycles.

He believed that if the rate of monetary growth could be kept stable,

economic growth would also be kept stable. Floating the dollar

eliminated foreign money flowing in and out of the economy, thereby removing

international sources of disturbance to the growth of the money

supply. For the Federal

Reserve, floating the dollar preserved its foreign reserves. Also, it

allowed American banks to continue to lend without restraint. Again, it

was a policy that treated the symptom and not the cause. Under the floating

exchange rate system, foreign currency continued to be required to pay for

the additional imports generated by the growth of bank credit. However,

instead of depleting the foreign reserves of the Federal Reserve, the wider

economy was required to finance the additional imports. It did this

through the sale of equity (selling off the farm) and the accumulation of

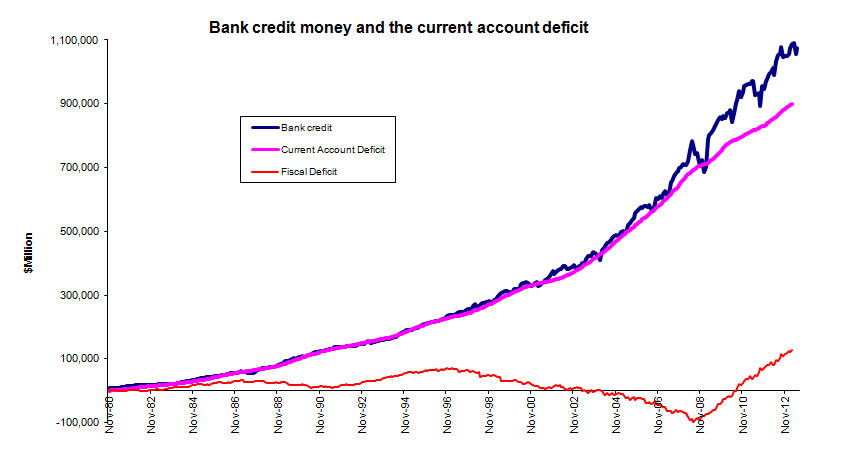

foreign debt. Figure 3 charts the

growth of bank credit in the USA and the accumulated current account deficit,

together with the fiscal deficit (which some economists claim to be the cause

of US current account deficits.)

Figure 3: USA

growth in bank credit, accumulated current account deficit and fiscal deficit Figure 3 illustrates

how closely the current account deficit has followed the growth of bank

credit for the last 25 years. Over that period, the current account

deficit has grown at an average rate of $0.8 billion per day. The cost

to the economy of bank credit under the floating exchange rate system is

clearly visible. The Formula for the

Current Account Balance provides a more detailed explanation of the

relationship between bank credit and the current account deficit.

It is worth noting

at this point that the current account deficit has been independent of the

fiscal deficit, or surplus. When the fiscal budget was in surplus,

between 1998 and 2001, the current account deficit continued to rise, and did

so more rapidly. When the fiscal deficit turned from surplus to

deficit, it had no effect on the current account deficit. Since 2008, private

borrowing from the banking system has declined. However, government

borrowing from the banking system (the Federal Reserve) has increased. This

has resulted in the current account deficit continuing to rise despite the

reduction in the growth of private bank credit. America is not

unique with respect to the relationship between the growth of bank credit and

the current account deficit. Figure 4 illustrates the same relationship

in Australia. Also, it is apparent that there is no direct relationship

between the fiscal deficit and the current account deficit.

Figure 4:

Australia, growth in bank credit, accumulated current account deficit and

fiscal deficit As for America,

Australian data for the growth of bank credit must be put together from the

available statistics. Changes to the Australian data series in January

2000 has meant that some other non-monetary assets have been included with

the bank lending statistics. Therefore, since 2000, it has not been

possible to accurately identify the growth of bank credit. This has

meant that the graph of bank credit has not been as closely aligned to the

graph of the current account deficit, as it was before 2000. However, the Reserve

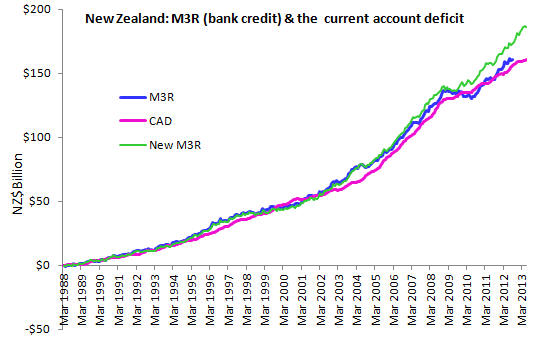

Bank of New Zealand publishes what it calls the M3R data series defined as

the money supply financed from domestic sources; namely bank credit.

This is illustrated in Figure 5. It clearly shows a direct relationship

between the growth of bank credit and the current account deficit. (New

Zealand introduced a new M3R series in October 2010 which is shown together

with the old series so that they can be compared.)

Figure 5: New

Zealand, growth in bank credit and the accumulated current account deficit The Philippines had

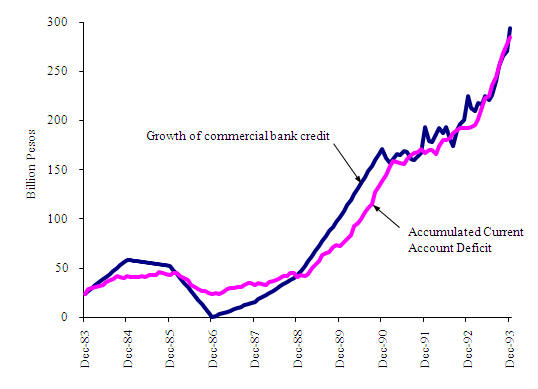

a similar relationship as shown in Figure 6. However, the Central Bank

of the Philippines now intervenes in the foreign exchange market to stabilize

the currency. Since 2003, the Philippines have experienced current

account surpluses and higher rates of economic growth.

Figure 6:

Philippines, growth in bank credit and the accumulated current account

deficit Inflation and

unsustainable credit growth Since 1995, the

relationship between the growth of bank credit and inflation in America can

be defined according to the following formula:

Pt/P0 = √((Lt/L0)/(Yt/Y0))

(If you see an "H" in this equation, the "H" represents a

square root sign.) Where:

Pt is the price at time t;

P0 is the initial price when t

= 0;

Lt is the total amount of bank credit at time t;

L0 is the initial amount of bank credit when t = 0;

Yt is the real level of national

income or GDP at time t; and

Y0 is the initial real level

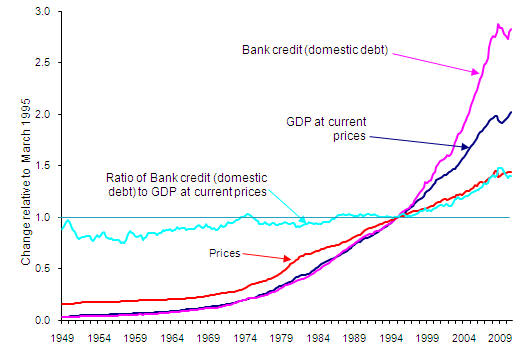

of national income or GDP when t = 0. Figure 7 compares

the official consumer price index with the index generated, using the above

formula. Similar relationships can be found for Australia and New Zealand.

Figure 7: USA

official consumer price index and modelled inflation Essentially the

equation says that inflation is equal to the square root of the growth of

bank credit relative to the growth of real gross domestic product. It

also reveals that bank credit is growing faster than gross domestic product

at current prices. That is:

Lt/L0 = (Yt/Y0)(Pt/P0)2 Before 1995, total

American bank debt grew roughly in proportion with gross domestic product

(GDP). However, since 1995, domestic American debt has been growing at

a faster rate than GDP, as shown in Figure 8. Figure 8 compares the

ratios of:

The capacity of the

economy to repay debt depends upon its income, or GDP. If its debt is

growing faster than its GDP, then eventually the economy will reach a point

at which the debt will be unsustainable because the cost of servicing the

debt will exceed its capacity to do so. At that point: ·

borrowers will default on their bank debt; ·

banks will reduce lending; ·

bank credit and the quantity of money would cease to grow; ·

the rate of economic growth would decline; and ·

debt that otherwise

would have been sustainable would become unsustainable. This would produce a

major recession and the failure of banks.

The "global

financial crisis" is likely to have been such an event for

America. It followed a period of rapid credit growth and it was

precipitated by the inability of borrowers to repay their debts. The growth of the

accumulated current account deficit is roughly equivalent to the growth of

domestic bank debt, as was shown in Figure 3. As much of the current

account deficit is financed with foreign debt, the growth in foreign debt

relative to GDP would have mirrored the growth of bank credit relative to GDP

shown in Figure 8. Hence, foreign as well as domestic debts are growing

faster than GDP. The growth of these

two types of debt is exacerbating the unsustainable nature of the current

monetary system. The global financial crisis may have been a transitory

monetary crisis and the current monetary system may be able to continue a

little while longer. However, if the monetary system is allowed to

continue as it has been, eventually, there will be a catastrophic financial

crisis that will destroy the monetary system and the economy as we know it. Change in monetary

policy in 1995 It is not totally

clear what aspect of monetary policy has changed since 1995 to increase the

ratio of bank debt to GDP in the US. One possibility is that up until

1995, the Federal Reserve had been intervening in the foreign exchange market

to manage the value of the American dollar (see the Plaza

Accord). Since then, it has changed and adopted a more “pure”

float. Australia

implemented the floating exchange rate system in December 1983. It

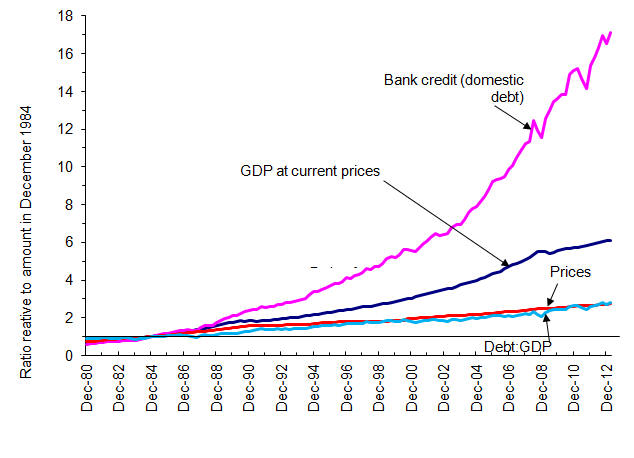

appears, from Figure 9, that in Australia’s case, bank credit has been

growing more rapidly than GDP since the float.

Figure 9: Australia

Ratio of domestic debt to GDP at current prices This suggests that

there have been some differences in the way America initially implemented the

floating exchange rate system, or monetary policy, compared to

Australia. However, since 1995, America and Australia’s systems have

been similar and they have behaved in an identical manner. Although the ratio

of bank credit to gross domestic product has more than doubled in Australia

since it floated the exchange rate, it has not yet reached the point where

the capacity to repay debt has been exceeded. This suggests that

initially, Australian borrowers may have been borrowing lower amounts

relative to their capacity.

Conflict of interest We can only

speculate on the real reason for the introduction of the floating exchange

rate system in America. The US Federal Reserve consists of a central

board of governors and twelve districts, each with its own board.

Frequently, former chief executives of banks progress to become board members

of their district Federal Reserve. Only one member of the seven Federal Reserve Board of Governors may be

selected directly from one of the twelve district boards. In making

appointments to the Board

of Governors, the President is directed by law to select a "fair

representation of the financial, agricultural, industrial, and commercial

interests and geographical divisions of the country." However, it

appears that most board members have had a prior

association with the Federal Reserve and/or the commercial banking

industry. Also, many have had an association with Harvard

University which has a particular neo-classical approach to monetary policy.

The key committee

controlling monetary policy is the Federal Open Market Committee

(FOMC) consists of 12 members. In addition to the seven members of the

Federal Reserve Board of Governors, there are five Federal Reserve Board

district presidents, one of whom is the president of the Federal Reserve Bank

of New York. Hence, it is bankers who have been predominantly responsible for

US monetary policy. In the early 1970’s,

the FOMC members would have been caught in a dilemma because of their

conflict of interest. They needed to preserve the foreign reserves of

the Federal Reserve. However, they would have been reluctant to

implement policies that would have restricted the lending activities of

banks. Such policies would constrain bank profitability, an outcome

that they would find uncomfortable. Therefore, they may have considered

that floating the exchange rate system addressed

their concerns. The Chairman of the Board of Governors was closely

associated with Milton Friedman, an economist promoting the floating exchange

rate system as a means of quarantining the money supply from international

influences, thereby allowing a policy of monetary targeting. For the

Board, it was a means of retaining their liberal lending policies and preserve the Federal Reserve's foreign

reserves. President Nixon,

having won the 1972 presidential election with the support of the banking

system (the Federal Reserve and the banks) may have been obliged to give the

Federal Reserve what it wanted. He would not have received any

opposition from the Treasury. Paul Volker

was the under-secretary of the Treasury for international monetary affairs at

that time. Before Treasury, Volker had worked for the Federal Reserve

Bank of New York. Also, he had been a vice president with Chase Manhattan

Bank.

The Harvard

connection provided the theoretical justification for the floating exchange

rate system. It also provided the rational for allowing the collapse of

American industries. Their failure was attributed to their own

incompetence: their inability to compete on world markets. This spin

diverted attention away from the limitations of the floating exchange rate

system: a system that in response to export growth,

requires imports to rise and displace domestic products (thereby undermining

domestic industries). Increasing the

current account deficit While the floating

exchange rate system prevented the depletion of foreign reserves, it also

prevented export growth from adding to foreign reserves and creating

additional money. That is, it prevented the country from earning any

additional income from the growth of exports. Before the dollar

was floated, the growth in export revenue would have contributed to national

income and savings (represented by the growth of foreign reserves).

Those national savings would have offset some of the additional spending

generated by the growth of bank credit (also called investment). After

the float, bank credit continued to enable people to buy more than they

produced, which continued to cause current account deficits. The floating

exchange system not only prevented the depletion of foreign reserves, it

prevented the accumulation of foreign reserves. Therefore the floating

exchange rate system prevented the growth of national savings that could have

offset the spending (investment) financed by the growth of bank credit.

As a result, floating the dollar increased the magnitude of the current

account deficit to the same amount as the growth of bank

credit. Dependence on bank

credit Under the floating

exchange rate system, the main source of new money has been from the growth

of bank credit. The economy needs additional money to facilitate

economic growth. Therefore, under the floating exchange rate

system, the economy requires banks to continually increase lending to provide

the stimulus to the economy to enable it to grow. Bank credit

continued to grow after the exchange rate was floated, reaching a growth rate

of 17.4 per cent in August 1973. Since then, it has not returned to that rate

of growth. The rate of monetary growth declined to just 2.9 per cent

per annum in August 1975 as shown in Figure 10. This decline in the

growth of bank credit, together with the elimination of additional income

from trade (brought about by floating the dollar) combined to cause the

recession known as the “oil crisis”. Since the float, the growth of

bank credit has largely determined the rate of economic growth and

inflation.

Figure 10: The

rate of growth of US bank credit, Jan. 1948 to Jan. 2013 Economic growth The problem

considered up until now relates to the growth of domestic and foreign

debt. However, that problem represents only the tip of the

iceberg. The policies implemented in 1973 to curtail the loss of

foreign reserves restrained trade within America and between America and the

rest of the world. Although the cost of these

restrictions have been astronomical, any objection has been silenced,

particularly by the financial sector which has profited from the growth of

credit. The financial sector has praised the merits of the market

determined exchange rate system and sought to associate it with free markets

and democracy. In reality, the

floating exchange rate system is anti-trade and restricts free markets.

It may be illegal because it contravenes anti-trust legislation such as the Sherman

Act. It is restraining trade and commerce, particularly with

foreign nations.

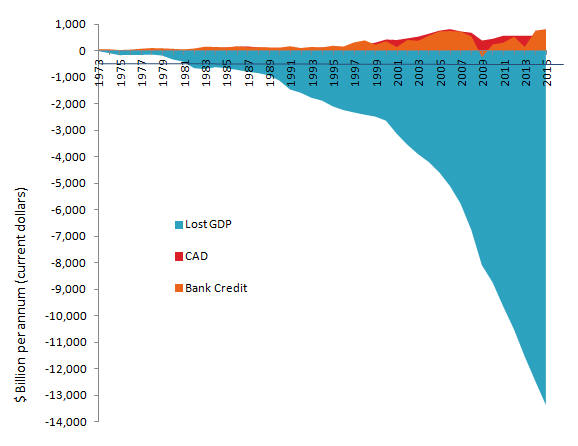

The cost of the

floating exchange rate system in terms of income, employment and social

welfare is significantly greater than the $0.8 billion per day average

increase in foreign debt. America’s real GDP could be at least 60 per

cent higher than it is today if it had maintained the average real rate of

economic growth experienced in the 25 years prior to 1973. On that basis, the

real cost of the floating exchange rate system is currently about $28 billion

per day in lost production and income in America alone. Figure 11

shows the lost GDP in America relative to the current account deficits and

the annual growth in the amount of bank credit (debt to the banks) to

December 2015.

Figure 11:

Annual lost GDP, current account deficit and growth of bank credit in America As mentioned earlier

and shown in Figure 1, one of the areas where the reduction in real income is

clearly evident is on real wages. The average real wages of American

workers are currently more than 10 percent below the level they were in

1973. This is despite the massive improvement in technology since

then. If the real wages of non-farm workers in America had continued to

rise from 1973 as they had in the previous 9 years, they would be about 80

per cent higher than they are today.

US Trade and the

Floating Exchange Rate System As mentioned above,

floating the dollar prevents money from being created through national

savings. Instead, the money from increased exports inflates the value

of the US dollar. The higher value of the dollar reduces export income and

raises imports. To achieve those increases in imports, the floating

exchange rate system requires Americans to shift their spending from domestic

products to imported products. The floating exchange rate system

achieves that outcome by making imports cheaper, relative to domestic

products. Manufacturing and

other import competing industries have been devastated by the shift in demand

from domestic products to imports. As a result, American industry has

been undermined. The industrial centres affected by the floating exchange

rate system are now collectively called “the Rust Belt”. The demise of

domestic manufacturing industry has been extensive. Even the American

auto industry has been threatened with extinction. The auto industry

recently had to rely upon government support to survive. If these

industries had prospered rather than been undermined by the exchange rate

system, America’s GDP and economic welfare would have been significantly

enhanced. These industries did not cause their own demise. They

are the victims of a monetary system that inherently functions to restrict

trade and destroy them. Equilibrium and the

export multiplier Floating the dollar

changes the way the economy achieves international balance of payments equilibrium;

that is, achieves equality between international payments and receipts.

Under the fixed

exchange rate system, if America increased its exports, more money would pour

into the economy, thereby raising incomes. As incomes rose, Americans

would buy more imports. International equilibrium would be attained

when American incomes had been augmented sufficiently to increase the level

of spending on imports to the same level as the revenue from exports. For example, let us

assume that the economy was initially at equilibrium and Americans spent 5

per cent of their income on imports. Also, let us assume that the level

of exports increased by $10 billion per annum. International

equilibrium would be attained again when US incomes had increased by an

additional $200 billion per annum. At that point, spending on imports

would have increased to $10 billion, to equal the additional income from

exports. It was largely the disequilibrium in international trade that

brought about the stimulus for the post war economic boom in America under

the fixed exchange system. (See: Impact of the

floating exchange rate system on employment and growth.) Under the floating

exchange rate system, equilibrium is attained instantaneously through the

exchange rate. If exports were to rise by $10 billion, the exchange

rate would appreciate to make imports cheaper until spending on imports

increased by $10 billion. There is no opportunity for disequilibrium

to generate economic growth. Equilibrium is achieved without any

increase in national income. The additional $10

billion in income that the exporters earned would have been offset by a $10

billion reduction in spending on domestic products which would have shifted

to imports instead. Thus the rise in exports and imports represent a

loss of income to American industries supplying the domestic market. Therefore, the

floating exchange rate system removes the stimulus previously received from

export growth because the additional export revenues are acquired at the cost

of lost revenue to the American industries competing with imports. The

floating exchange rate system ensures that there is no additional money

entering the economy from exports and other international transactions.

The export industries may prosper from increased export income but that

income is at the cost of lost income for import competing industries. Floating the

exchange rate has killed the goose that laid the golden egg for the US

economy. Globalization and

Competition The floating

exchange rate system requires that the exchange rate appreciate until imports

and other foreign payments equal exports and other foreign receipts.

Therefore, if all domestic industries were to cut costs to be more

competitive and raise exports their efforts would be thwarted by an even

higher exchange rate. Also, higher

exchange rates make American products less competitive on world markets, and

reduce the incomes of exporters. Therefore, the higher exchange

rate undermines export industries as well as import competing

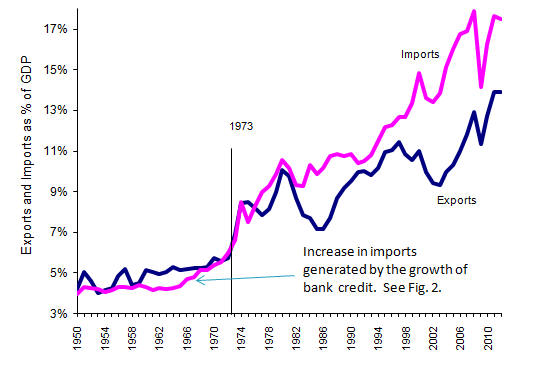

industries. Figure 12 shows

American exports and imports as a percentage of GDP. Before 1973,

American imports and exports were stable and below 6 per cent of GDP.

Before the float, any increase in exports would have stimulated the whole

economy, so that GDP increased with export growth. After 1973, any

increase in exports stimulated an equivalent increase in imports.

Export growth no longer stimulated the domestic economy to generate economic

growth. Also, the higher exchange rates undermined the demand for

products from domestic import competing industries. As a result, the

growth in exports and imports exceeded the growth of the remainder of the

economy. This phenomenon is part of what has been called globalization.

Figure 12: US

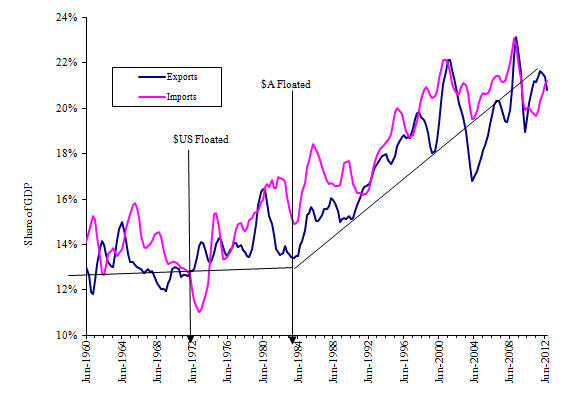

exports and imports as a percentage of GDP Australian

international trade experienced a similar trend. In 1973, the Australia

dollar was tied to the American dollar. Hence, when the US dollar was

floated, Australia experienced an increase in the relative size of imports,

similar to the US. When Australia floated in 1983, instead of exports

stimulating growth in the whole economy, the relative size of exports increased

significantly as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13:

Australian exports and imports as a percentage of GDP Unemployment Since the exchange

rate was floated, the average rate of unemployment in America has increased

by one third, from 4.8 per cent to 6.4 per cent. This increase in the

rate of unemployment together with the lower level of wages has contributed

to the increased level of poverty in America. Figure 14 plots the level

of unemployment in America and provides a comparison of unemployment rates

before and after the floating exchange rate system was

introduced.

Figure 14:

American unemployment rates (12 month rolling average) Prices Inflation has

increased, also, since the dollar was floated. Figure 15 charts the US

consumer price index since 1939. It shows a clear rise in the rate of

inflation since 1973.

Figure 15: American consumer price index (1982-84 = 100) Interest rates Long term interest

rates have initially increased significantly following the float. From

1953 to February 1973, interest rates for 10 year government securities have

averaged 5.2 per cent. Since April 1973, the average has increased to

7.3 per cent, a rise of forty per cent. Interest rates have been falling

since September 1982. Since January 2000, average long term interest

rates have fallen back to an average of 4.3 per cent. That has

reflected short term interest rates that have been lowered in an attempt to

stimulate the economy out of recession. Figure 16 charts the interest

rate of ten year Government securities since April 1953.

Figure 16: Interest rates US 10 Year Government

securities Legislated

objectives Section 2A of

Federal Reserve Act requires the Federal Reserve, through the Board and the

Federal Open Market Committee, "to promote effectively the goals of

maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest

rates". As evident from Figures 14, 15 and 16, since 1973, the

Federal Reserve has been less able to achieve these objectives.

Unemployment has been high, prices have been rising rapidly and long term

interest rates have not stabilized at moderate levels. While the

current form of the floating exchange rate system continues to be in force,

it will not possible for the Federal Reserve to be effective in achieving its

legislated objectives. Therefore, floating the dollar has restricting

the ability of the Federal Reserves' ability to achieve its objectives. International Trade

and the Floating Exchange Rate System While the proportion

of GDP earned from exports have nearly doubled, international trade would

have been far greater if the exchange rate had not been floated. Higher

exchange rates have reduced exports and made American exports less competitive

around the world. This arrangements constitutes a

restraint of trade or commerce with foreign nations. This restraint of

trade has occurred in other countries that have floated their

currencies. Consequently, world trade has declined. This was evident

immediately after America floated its currency. Ship building

industries around the world collapsed as the decline in the growth of trade

reduced the demand for the additional shipping capacity being

built. Also, Professor Angus Maddison in his

book The World Economy acknowledge that

"world economic growth has

slowed substantially since 1973."

International

Strategic Acquisitions Countries exposed to

the floating exchange rate system have seen their manufacturing industries

destroyed. Also, their governments have been faced with reduced incomes

and rising costs associated with supporting their communities that have been

suffering from the poor state of their economies. In this weakened

state, these economies have been selling off strategic assets such as

infrastructure and major industrial assets. In some cases acquisitions

by foreign entities have been welcomed. Any possible threat to national

security has been disregarded. Also, sovereign

investment funds may be used to acquire strategic economic targets such as

mineral assets. In the event that economies that are currently

being restrained by the floating exchange rate system are released to

prosper, they may find that the mineral resources necessary for the expansion

of their industries are no longer readily available. Necessary reforms Money is the

economy’s software that drives its real hardware. Without an efficient

and effective monetary system, the economy’s hardware is likely to be left

idle. In the interests of the performance of the real economy, the

monetary system must be reformed. Also, as considered

above, the growth of debt under the current monetary system is unsustainable

and will eventually lead to the complete collapse of the financial

system. Therefore, it is necessary for the long term benefit of the

financial system that the monetary system be reformed. Governance –

conflict of interest The primary change

required to achieve a stable and sustainable monetary system is institutional

reform. Even if the Federal Reserve believed it was acting in the

national interest in 1973, America can no longer allow the foxes to be in

charge of the hen house. Government needs to

manage monetary policy; not the banks through the Federal Reserve. It

may not be necessary to totally abolish the Federal Reserve. However,

the Treasury, or some other government institution that does not have a

conflict of interest, needs to take control of monetary policy in the

national interest. Managing the Growth

of Bank Credit Under the floating

exchange rate system, any growth in bank credit is likely to lead to current

account deficits. That outcome can be avoided if banks are allowed to hold

foreign reserves and, in effect, lend those reserves. Such reserves

would generally constitute national savings; and lending such savings does

not cause current account deficits. Achieving such an

outcome may be more complex than it might first appear. Once savings

have been lent, there is little tangible evidence to show that they have

existed. This problem can be overcome by requiring banks to hold

minimum levels of foreign reserves, or gold, with a central monetary

authority and linking the level of lending to those reserves. In addition to these

reserve accounts, banks may be required to operate foreign exchange (or gold)

based interbank settlement accounts with the institution responsible for

interbank settlements. Banks could settle their accounts in US dollars.

However, any bank with a credit balance with another bank may wish to convert

those balances to foreign reserves so that it can increase its lending.

Banks must be able to honour such transactions. Requiring banks to hold

foreign reserves or gold ensures that the banks have the savings to fund

their lending. If a bank’s foreign

exchange settlement account were depleted, the inter bank settlement

institution would be able to call upon funds from that bank’s reserve account

to make up the shortfall. That action would trigger the suspension of

the bank’s authority to increase its lending, until such time as the reserve

account was replenished. Note that this does not require the complete

cessation of lending. The bank may maintain its total lending at the

current level; lending only that which has been repaid on the principal of

existing loans. By way of example,

banks may be authorized to lend, say, an additional $25,000 for every

additional ounce of gold, or foreign exchange equivalent, that they hold in

their reserve account with the central monetary authority. Therefore, a

bank with the equivalent of 10,000 ounces of gold in their reserve account

with the central monetary authority would be able to lend up to an additional

$250 million. The reserve account ensures

that savings are greater than lending and provides a trigger mechanism to

manage excessive bank credit. Capital and other financial requirements

for prudential purposes of a financial institution are additional to these

macro-economic requirements. Managing the

Exchange Rate and Inflation The floating

exchange rate system manages the exchange rate to ensure international

receipts and payments are equal. Under that system the foreign exchange

market is required to be constantly cleared: banks are required avoid holding

foreign exchange. Under the proposed

system, banks would be required to hold foreign exchange. Foreign

exchange is required for their reserve accounts and their interbank

settlement accounts. In addition, banks may hold foreign exchange

in their own right for their own purposes, such as to meet customer demand

for foreign exchange. These changes to the

foreign exchange requirements would make the current system for setting the

exchange rate unworkable. However, it is not necessary to return to the

fixed exchange rate system. To give direction to

the foreign exchange market, incentives can be provided for the market to

manage the exchange rate to achieve economic objectives such as full

employment. If we continue with the example in the section above,

the amount that banks may lend per ounce of gold equivalent could be reduced

by $1,000 for every one per cent of unemployment. If unemployment

were 10 per cent, then the amount banks would be allowed to lend would be

reduced by $10,000 per ounce of gold equivalent. In that case, they

would be limited to lending an additional $15,000 for every additional ounce

of gold ore equivalent foreign exchange in their foreign reserve account. Banks make profits

from holding loans rather than reserve assets. To maximize their

profits they would seek to drive the exchange rate to a level that minimizes

unemployment so as to maximize their lending relative to their

reserves. Given such an

incentive, banks could drive the exchange rate excessively low, causing

inflation. To offset the incentive to devalue excessively, a similar

incentive mechanism could be established to manage inflation. For

example, the amount banks may lend per ounce of gold could be reduced by

$1,000 for every one per cent of inflation. Thus, if inflation

were 5 per cent, the amount banks would be allowed to lend per ounce of gold

(or foreign exchange equivalent) would be reduced by $5,000. If

unemployment were 10 per cent and inflation 5 per cent, banks would be able

to lend an additional $10,000 for every additional ounce of gold in their

foreign reserve account. In such a financial

environment, banks would act to manage the exchange rate and their lending in

a manner that maximizes employment and minimizes inflation. Interest rates With such a system

managing monetary growth, interest rates would no longer be an instrument of

monetary policy. The market would act to minimize inflation without

direct action from the Federal Reserve. This allows the finance market

to set interest rates. If there were a shortage of available credit,

interest rates would rise, encouraging savings, discouraging borrowing and

attracting foreign investment funds. Such outcomes would increase the

ability of the financial market to meet the demand for credit. If the

capacity to lend exceeded the demand, interest rates would decline. The

financial market would respond to adjust interests

rates and eventually drive it towards a stable sustainable rate. Conclusion The Global Financial

Crisis has created some urgency in addressing the failings in the American

monetary system. However, that crisis is just one of the many

symptoms of the flawed monetary system that has been undermining the American

economy. Unless the root causes of these problems are addressed, the

problems will persist, and grow. If the American nation is to prosper

in future, it must change its monetary system to one that is conducive to

economic growth and prosperity. Most likely, many

Americans will deny that the problems explained in this paper exist.

That is a normal defensive human reaction. However, American

manufacturing industries have collapsed. The real wages of US workers

have declined. The US, which had financed the reconstruction of Europe

after World War II, is now deeply in debt to the rest of the world.

These changes did not just evolve. They have been engineered.

They are the result of changes to economic policy and unless the policy is

changed, US industries will continue to decline and US foreign debt will

continue to rise. A similar incident

occurred after the First World War. Britain had been a world political and

economic power. It had devalued the British pound early in the war and

the Chancellor, Winston Churchill, re-valued it after the war. That

revaluation caused unemployment and severely damaged the British

economy. Although Churchill later realized he had made a mistake, it

would have been too embarrassing for him and the government to have admitted

the mistake and devalued the pound. So the nation suffered and the

British Empire collapsed. As explained above,

the US does not need to return to a fixed exchange rate. But, if it

does not manage the growth of bank credit, like the UK, it's

economy will continue its decline and become a shadow of its former

self. Leigh Harkness "The

refusal of King George III to allow the colonies to operate an honest money

system, which freed the ordinary man from the clutches of the money manipulators was probably the prime cause of the

revolution." Benjamin Franklin [1] Original charts and data for

US graphs are available at: http://www.buoyanteconomies.com/USACAD.xls. [2] These same problems are now

causing the excessive rise in domestic and foreign debt. [3] These consequences include

the demise of import competing industries and the reduction in the rate of economic

growth. [4] The lending manager of the

Bank of Tonga (originally from the Bank Hawaii) later expressed his

appreciation of the Tongan scheme saying that the guidelines enabled them

know how much money they could lend and it helped them

appreciate the effect of their lending on the economy. [5] See www.reservebank.to . [6] The term “national savings” relates to a specific type of savings

held in the form of foreign reserves. For example, China’s growing foreign reserves are

attributable to its national savings. These national savings are created when exports and other foreign income

exceed imports and other foreign expenditure. When a Chinese exporter earns additional export

income, that exporter may spend all those funds paying employees and buying materials. Although they as spending the

money, while those funds are being spent on Chinese products, they remain part of Chinese national savings. Impact of the

floating exchange rate system on economic growth, wages, employment and trade. An

introduction to the optimum exchange rate system The guided exchange rate system USA

Australia

New Zealand

Philippines First published: 3 July 2011 Last update: 2 October 2020 |