Buoyant Economies

Letter to Joe Hockey on the Intergenerational Report

Dear Mr Hockey

Thank you for the invitation of 7 March to provide feedback on intergenerational report and the direction of your economic policy. The major predicament that faces you and this country is the growth of debt. When you stated that “very few people can live on one household income and still pay the mortgages in the major capital cities,” you recognised that this is not a problem of just public debt: it relates to private debt, also.

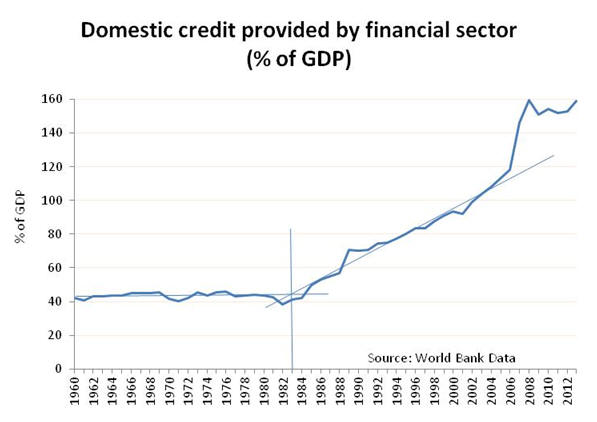

Below is a chart of the growth of that debt represented by the credit provided by the financial sector in Australia for more than 50 years as a proportion of GDP. The chart reveals that there was a major change in the growth of debt around 1983. Before then, debt grew at the same rate as GDP, and was stable at about 40% of GDP. After then, debt grew faster than GDP and by 2013, was equivalent to about 160% of GDP.

The difficulty that our economy is now facing is not a recent ailment. It was caused by changes in economic policies around 1983. Unless you rectify the condition caused at that time, you will not be able to rectify the predicament now facing Australia. For example, if were to you reduce the burden of public debt, you are likely to transfer that burden, in one form or another, to the private sector, which is already suffering from its own debt burden.

As you said: “the fact is, the trends are still there, the numbers are still there. . .; the challenges of the future are still there.” So, it is vitally important that we think outside the realm of economics written by the elite that wishes to blame the victims for their inadequate policies.

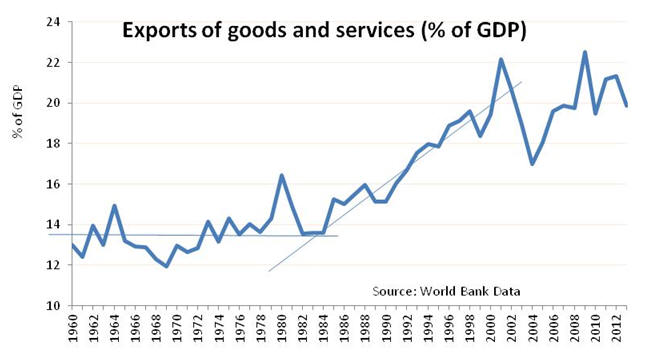

Associated with this rising debt crisis, is another significant change in the economy that began in the mid 198o’s, as shown in the following chart. Exports had remained relatively stable as a share of GDP at around 12% to 15% up until 1984. Since then they have increased to over 20% of GDP.

At first glance, rising exports appear to be a good thing. But this is not the case if they are not raising GDP. Up until the early to mid 1980’s exports were rising and they were raising GDP, also. After then, exports rose but they did not raise GDP in the way that they did before. If exports had increased GDP in the manner that they had before the mid 1980’s, Australia’s GDP would now be more than 50% higher than it is now. If that were the case, more people would be working, thereby reducing the cost to government of social security. Also, government tax revenues could be at least 50% higher, also.

Not only is government worse off, but the people of this country are worse off, because of the “reforms” made in the early to mid 1980s. The policies implemented in the early to mid 1980’s have been like a cancer, eating away at the economy. If the government were to further reduce expenditure and raise taxes, it would be spreading that cancer further into Australian life and the economy.

We are going to have make changes not in the way we live in order to preserve the very best of Australian life but changes to economic policy, in order to restore and enhance Australian life. It is essential for the welfare of the economy and the people of Australia that the economic cancer introduced in the early to mid 1980’s be removed.

There were two major policy “reforms” implemented in the early to mid 1980’s that brought about these adverse outcomes for the Australian economy. The first was the deregulation of the banking system and the second was the floating of the exchange rate.

Elitist economists would say that the deregulation of bank lending allowed investment to expand and build the Australian economy. More astute economists would have recognised that the deregulation of the bank lending in Australia has inflated home prices so that very few people can live on one household income and still pay the mortgages in the major capital cities. The ability to live on one household income and still pay the mortgage was one of the better attributes of Australian life that now has been lost for most Australians.

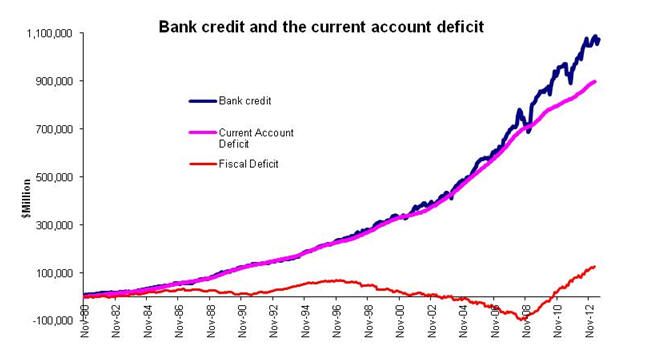

Another feature of bank lending is that it has caused large current account deficits. If savings were the only source of money to lend, then Australian spending would have been limited to income, or production. The borrowers would be spending money that lenders could have spent. It is only when additional money is created that lending can exceed savings, thereby enabling spending to exceed income.

The current account deficit represents the amount by which spending has exceeded income. Data from the Reserve Bank of Australia indicates that the current account deficit has been equal to the growth of bank credit. Since 2002, the Bank has broadened the coverage of some of its monetary reports to include non-bank credit. Even so, the following chart continues to show the close relationship between bank credit and the current account deficit.

Also, the chart reveals that the current account deficit is unrelated to the fiscal deficit.[1] As shown above, the current account deficit continued to rise with credit growth between 1996 and 2008 while there were fiscal surpluses.

The fact that bank lending creates additional money is described by J.M. Keynes in his Treatise on Money and is recognised by the Bank of England[2]

Before the floating of the exchange rate was introduced, when Australia increased its exports, more money would flow into the economy, stimulating the whole economy. After the float, when the country increased its exports, the exchange rate would rise, reducing exporters’ income. Also, the higher exchange rate would make imports cheaper so that Australians would shift their spending from Australian products to imports. Both these effects contributed to the decline in the rate of economic growth in Australia following the float and undermined Australian industries.

The exchange rate was floated to protect foreign reserves which had declined due to the deregulation of bank lending. When Australia’s exchange rate was fixed, the banking system would convert the foreign currency entering the economy from exports, etc., into Australian dollars. The foreign money was held as foreign reserves. The new Australian money would flow throughout the Australian economy, raising incomes. Eventually, that money would be spent on imports. Then, the banking system would draw on its foreign reserves to convert the domestic currency back into foreign currency to pay for those imports.

In addition, bank lending contributed to the money flowing through the Australian economy. Eventually, that money would be spent on imports, also. Then, the banking system would draw on its foreign reserves again to convert the domestic currency into foreign currency and pay for those imports. If bank lending were excessive, it would deplete foreign reserves, and the country would need to borrow to finance its imports. To avoid the need for such borrowing, bank lending was regulated.

When the government deregulating bank lending, it caused Australia’s foreign reserves to be depleted, resulting in speculation on the value of the Australian dollar. In response, the government “floated” the Australian dollar. Much was made of the “market” determined exchange rate. However, its real purpose was to require international receipts and payments to be equal and thereby curtail the leak of foreign reserves caused by the growth of bank credit. Bank credit continued to cause the economy to buy more than it produced, but that deficit had to be financed with foreign capital inflow, not from the banking system’s foreign reserves.

Floating the currency meant that the only source of monetary growth was bank credit. Income from exports no longer added to foreign reserves. Nor did they provide additional money and income to stimulate the economy. Thus, the only way to stimulate the Australian economy was for the economy, including government, to go deeper into debt. If government were to reduce its debt, without increasing private debt, it would withdraw money and income from the economy.

Another facet of this predicament relates to the quantity theory of money. The theory states that the money supply times the velocity of circulation is equal to the number of transactions in the economy times their price. As incomes and prices rise, the economy needs a proportional increase in the money supply and, therefore, in debt. However, the additional transactions required to service the increasing debt also requires additional money, and therefore, additional debt. Thus debt must rise faster than the rate of economic growth (as shown in the first chart). The fact that debt is required to grow faster than the economy means that debt must grow faster than the capacity of the economy to repay that debt. Eventually, as we have seen in the USA, UK and Europe, debt must exceed the capacity of the economy to service that debt, and cause a financial crisis.

The potential intergenerational calamity that you wish us to consider is just one symptom of a much larger impending catastrophe. If you treat the symptoms and not the causes, you will not be preventing that catastrophe: you could bring it on.

The relationship between the growth of bank credit on the current account deficit was considered in the Treasury in the later half of the 1980s. At that time, the official response to the data was to treat is as a coincidence. Even so, some Treasury officers, including myself, considered the matter further and devised a possible solution. In 1993, I accepted a redundancy offer from the Treasury and in 1995, I presented a series of papers on the problem and the solution.[3] The solution relies upon providing incentives to the foreign exchange market to manage the exchange rate at a level that maintains sufficient demand for domestic products so as to attain full employment. Also, it manages the growth of bank credit to avoid raising net foreign debt.

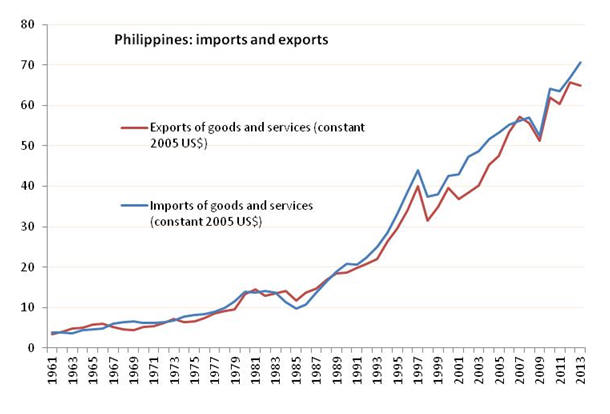

Policies that allow the income from international trade to stimulate the domestic economy have proved successful in other economies, such as Germany and the Philippines. Germany, as part of the Euro Zone, has been able to enjoy a lower exchange rate than it would have had, if it had its own currency. This has enabled it to prosper from money international trade, not just bank credit. The Central Bank of the Philippines states that it intervenes to stabilise its exchange rate. That intervention injects money into the economy. Also the Bank limits the use of bank credit to finance the purchase of real estate, enabling the Philippines to attain current account surpluses since 2003.

The following chart shows that spending on imports in the Philippines has fallen from about 60% of GDP in 1997 to 32% in 2013. Also, exports have fallen from 51% of GDP to 28% in 2013. The Central Bank’s policies have contributed to an increase in per capita income in the Philippines of 41% in the 10 years to 2013 compared to 17% over the previous 10 years. Australian per capita income has increased only 16% in the last 10 years.

Despite the reduction in imports and exports as a proportion of GDP, both imports and exports have continued to rise in the Philippines as shown in the following chart.

Mr Hockey, you said that you are reaching out to the community and engaging in a conversation about Australia’s future. The fundamental point is this: if we maintain the same policies, we will continue to go in the same direction, increasing debt and undermining the future of Australian industries.

We need to change our monetary policies now, before it is too late. We need to treat the causes of our economic difficulties, not the symptoms. The quality of life Australian have today is not going to be there tomorrow, if you do not act to rectify the policy errors of the past.

You can't put your head in the sand and expect that the world's going to change. You've got to be part of that change.

Yours sincerely

Leigh Harkness

[1] Links to the data and to similar charts for other countries are available from: www.buoyanteconomies.com/AustCADMoney.htm

[2] See Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin Money creation in the modern economy available at: www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

[3] Available at: www.buoyanteconomies.com/PAPER3.pdf

Home Other issues A more detailed description of the technicalities of debt

Impact of the floating exchange rate system on economic growth, wages, employment and trade.

USA Australia New Zealand Philippines

Last update: 27 March 2015