Buoyant Economies

The guided exchange rate and

liquidity system

Also, some central banks are familiar at guiding the economy using interest rates, particularly under the floating exchange rate system and wish to maintain that level of control. Furthermore, the legislation under which central banks may work may not allow them to leave the economy fully open to the market.

The guided exchange rate and liquidity system (GERLS) is a market determined variable exchange rate system, as is the floating exchange rate system and the optimum exchange rate system. It facilitates the management of monetary flows to ensure balance of payments stability and provides a means for the central bank to influence the exchange rate to ensure international competitiveness and maintain economic growth.

GERLS manages the growth of bank credit with an approach based upon the fractional reserves banking system linked to a reserve fund. It requires commercial banks to hold a “Reserve and Settlement” account with the central bank. Inter-bank settlements must be made through these accounts. (These can be separate accounts and may be with different institutions: the reserve account may be with the central bank and the settlement account with the inter-bank settlement authority.)

Commercial banks would be able to increase their lending by, say, twenty thousands dollars (or units of local currency) for every additional unit of foreign exchange (or gold) that they add to their Reserves and Settlements account. The central bank would be free to vary the amount of additional credit banks could provide relative to the increase in their foreign exchange (or gold) holdings.

Commercial banks would be able to increase the balances of their Reserves and Settlements account by selling foreign exchange to the central bank and thereby obtaining a credit in their Reserve and Settlement account. Commercial banks would not be able to increase the balance of their Reserve and Settlement account by selling any government or private securities to the central bank.

The central bank could offer to buy and sell foreign exchange at a specified rate. That exchange rate would be the central bank’s guiding exchange rate.

The central banks of most countries are likely to set their guiding exchange rates in terms of a basket of currencies. The guiding exchange rate would be an instrument of monetary policy and the central bank would be unlikely to vary it unless it had reason to change it. I would expect that a central bank would choose to vary the guiding exchange rate in much the same way as they currently vary interest rates: at irregular intervals and in small increments. Even so, it is likely that the exchange rate for specific currencies would vary according to movements in those exchange rates relative to the basket of currencies used to define the guiding rate.

The central bank’s offer to exchange foreign currency at a specified rate means that there would be little exchange rate risk for commercial banks to hold foreign exchange. If commercial banks were allowed to hold foreign exchange, it may reduce the need for them to trade foreign currency with the central bank. To this end, it would be advisable to allow commercial banks to hold foreign exchange. It may contribute to exchange rate stability, allowing commercial banks to trade foreign currency with other traders in the foreign exchange market.

The central bank’s holdings of foreign reserves should be greater always than the sum of the Reserves and Settlements accounts and currency in circulation.

The central bank would not be guaranteeing the value of the local currency. It would only guarantee to pay the guiding exchange rate on the funds held in the commercial banks’ Reserves and Settlements accounts. Therefore, it does not hold any significant exchange rate risk. If it chooses to devalue, the value of its foreign exchange holdings (assets) would increase (in terms of domestic currency) and its liabilities to the commercial banks would remain the same. It would only be if the central bank chose to revalue the currency that it would experience any loss on foreign exchange. In that case, it would be choosing to make that exchange rate loss.

For example, if it chose to appreciate the exchange rate by 5 per cent, the value of its foreign assets would decline in value by 5 per cent relative to its domestic assets and liabilities. Therefore, it would suffer a loss equivalent to 5 per cent of its foreign assets in terms of domestic currency. Alternatively, if it depreciated the currency by 5 per cent, its foreign assets would rise in value by 5 per cent relative to its domestic assets and liabilities and it would profit from the appreciation.

The central bank would not be setting the exchange rate of the local currency. The market would be free to trade at, above or below the central bank’s guiding exchange rates. Of course, if a bank with foreign currency were offered less local currency on the market than it could recover under the central bank’s guiding rate, the commercial bank would be likely to sell those funds to the central bank and credit its Reserve and Settlement account.

The central bank should pay interest on the balances of the Reserve and Settlement accounts. It would be free to vary that rate and would, thereby, influence market interest rates.

If a commercial bank with surplus funds in its Reserve and Settlement account were seeking to buy foreign currency and the market price were higher than central bank’s guiding exchange rate, the commercial bank may choose to buy the foreign currency from the central bank at the lower guiding rate. The central bank would not sell foreign exchange to a commercial bank if by doing so it would reduce the commercial bank’s reserves below the minimum amount necessary for the bank’s level of outstanding loans.

The central bank would not be participating in most international exchange transactions. The foreign exchange market would continue to persist for the usual day to day international transactions. The central bank’s guiding rate would only guide, not set, the value of the currency on the foreign exchange market.

The central bank would be free to enter the foreign exchange market at any time and buy or sell currency on its own account. If the central bank were to issue loans or buy securities, it too should have a Reserve and Settlement account. Loans to government in any form, should be governed by the same rules as apply to commercial banks.

Commercial banks wishing to buy local currency (notes and coins) from the central bank would pay for that currency with funds from their Reserve and Settlement account. The central bank would credit commercial banks’ Reserve and Settlements accounts for any currency returned.

To explain the process in more detail, let us assume that the following account is the consolidated balance sheets the commercial banks:

|

Assets |

$ B |

Liabilities & equity |

$ B |

|

Loans |

3000 |

Deposits |

2500 |

|

Other assets |

850 |

Other liabilities |

600 |

|

Reserve and settlement |

|

|

|

|

Buildings other fixed assets |

150 |

Capital |

900 |

|

Total |

4000 |

Total |

4000 |

Let us assume that the following is the balance sheets of the central bank.

|

Assets |

$ B |

Liabilities & equity |

$ B |

|

Foreign currency assets |

1400 |

Currency in circulation |

400 |

|

Local currency assets |

500 |

Foreign currency liabilities |

100 |

|

|

|

Reserve and settlement |

|

|

|

|

Other local currency liabilities |

1300 |

|

Buildings other fixed assets |

100 |

Capital |

200 |

|

Total |

2000 |

Total |

2000 |

Let us assume that under GERLS, the fractional reserves ratio is ten dollars of lending for every one dollar in the Reserve and Settlement account.

Assume that the commercial banks buy $10 billion of foreign exchange from their exporting customers and by doing so create a deposit of $10 billion. Their consolidated accounts would show these transactions as:

|

|

|

Debit $ B |

Credit $ B |

|

Foreign currency reserves |

10 |

|

|

|

|

Deposit |

|

10 |

In the consolidated accounts of the banking system, this will be shown as:

|

Assets |

$ B |

Liabilities & equity |

$ B |

|

Loans |

3000 |

Deposits |

2510 |

|

Other assets |

850 |

Other liabilities |

600 |

|

Foreign currency reserves |

10 |

|

|

|

Reserve and settlement |

|

|

|

|

Buildings other fixed assets |

150 |

Capital |

900 |

|

Total |

4010 |

Total |

4010 |

Now the banks sell their $10 billion of foreign currency to the central bank. In effect, the commercial banks would make the following entries in their consolidated accounts.

|

|

|

Debit $ B |

Credit $ B |

|

Reserve and settlement |

10 |

|

|

|

|

Foreign currency reserves |

|

10 |

This transaction exchanges one asset (foreign currency reserves) for another asset (reserve and settlement deposit with the central bank). As a result of this transaction, the consolidated balance sheet of the commercial banks would be:

|

Assets |

$ B |

Liabilities & equity |

$ B |

|

Loans |

3000 |

Deposits |

2510 |

|

Other assets |

850 |

Other liabilities |

600 |

|

Foreign currency reserves |

|

|

|

|

Reserve and settlement |

10 |

|

|

|

Buildings other fixed assets |

150 |

Capital |

900 |

|

Total |

4010 |

Total |

4010 |

For the same transaction, the central bank would make the following entries in its accounts.

|

|

|

Debit $ B |

Credit $ B |

|

Foreign currency assets |

10 |

|

|

|

|

Reserve and settlement |

|

10 |

As a result, the central bank’s balance sheet would be:

|

Assets |

$ B |

Liabilities & equity |

$ B |

|

Foreign currency assets |

1410 |

Currency in circulation |

400 |

|

Local currency assets |

500 |

Foreign currency liabilities |

100 |

|

|

|

Reserve and settlement |

10 |

|

|

|

Other local currency liabilities |

1300 |

|

Buildings other fixed assets |

100 |

Capital |

200 |

|

Total |

2010 |

Total |

2010 |

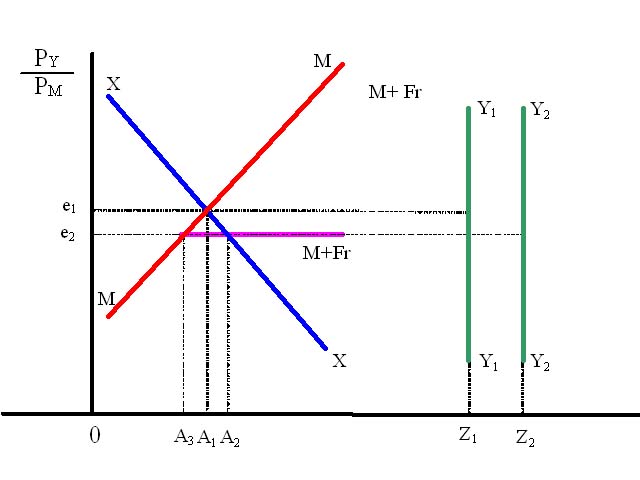

The effect of these transactions has been displayed graphically in Figure 1. Let us assume that there is initially no growth in bank credit and there are no net international capital flows. Exports, which could include remittances, are shown as the X-X line. Imports are given by the M-M line. Under the floating exchange rte system, the exchange rate would be at e1. Exports are equal to imports which are equal to 0-A1. Expenditure on and income from domestic production is equal to A1-Z1. National income is given by the Y1-Y1 line and is equal to the interval 0-Z1.

Figure 1. GERLS with increased foreign reserves and increased income

Now we introduce GERLS and the commercial banks take advantage of the central bank’s guiding exchange rate at e2 to buy $10 billion in foreign currency. The banks would sell this foreign exchange to the central bank because they would earn more in terms of local currency by selling the foreign exchange to the central bank than they would if they sold it on the market. Therefore, GERLS creates a cap shown as the M+Fr (imports plus foreign reserves) line. Even if there were no increase in the physical amount of exports, given the greater number of dollars paid for foreign currency with the lower exchange rate of e2, the value of exports increases from 0-A1 to 0-A2.

All exporters would want to be paid at the lower exchange rate offered by the central bank. This reduces the demand for domestic currency on the foreign exchange market and lowers the market exchange rate. The lower exchange rate makes imports relatively more expensive, so imports fall to 0-A3. The increase of $10 billion in foreign reserves sold to the central bank is represented by the interval A3-A2.

Domestic expenditure on domestic products rises from A1-Z1 to A3-Z1 . National income is made up of foreign income and domestic income, comprising exports of 0-A2 and income from domestic production A3-Z1. When these are added together, it means that national income has risen by the equivalent of the growth in foreign reserves, taking the level of national income from Z1to Z2 (made up of 0-A2 of export income and of A3-Z1 in domestic sales income).

Theoretically, these additional reserves would enable the banks to lend an additional $100 billion. But as the banks start lending, they increase the demand for imports, shifting the imports schedule to the right. Also, at the higher level of income, demand for imports has increased. These transactions are likely to reduce foreign reserves and keep in check the growth of bank credit.

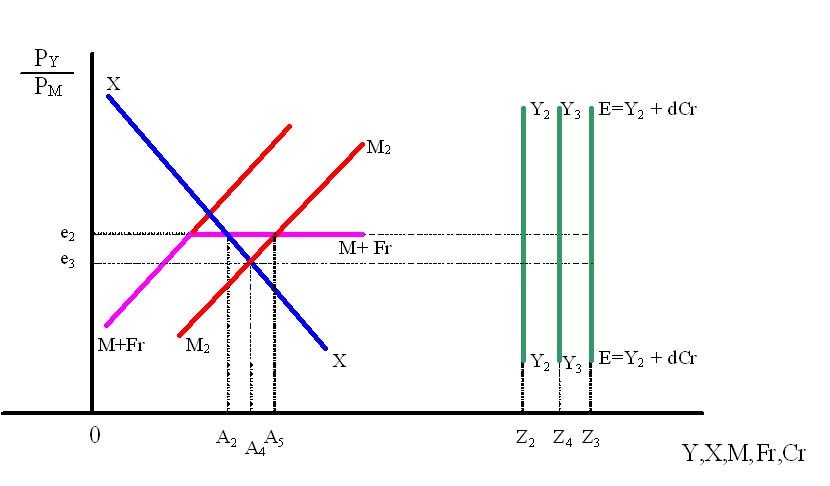

To consider this outcome, let us assume that the commercial banks increase lending by $15 billion and it is all spent on imports. Also, the increase in income raises expenditure on imports by $3 billion. The net effect is that the demand for imports has increased by $18 billion.

This outcome is presented in Figure 2. Demand for imports has now shifted to the right by $18 billion to M2-M2. This raises total expenditure to the E – E line which is equal to income represented by the Y2-Y2 line plus the growth in bank credit.

If the foreign exchange market were to fully determine the exchange rate, the exchange rate would fall to e3. At that point, exports and imports would be at A4.

Rather than drive down the exchange rate, we will assume that the commercial banks decide to buy $8 billion of foreign exchange from the central bank to pay for the imports. In that case, the exchange rate stays at e2 with exports still at A2 while imports are at A5.

Figure 2: GERLS with reduction in foreign reserves and increased income

National income is made up of income from exports (0-A2), plus income from the sale of domestic products (A5-Z3). Although imports were greater than exports, national income rises from 0-Z2 to 0-Z4, equivalent to an additional increase of $7 billion. This increase in income is derived from the increase of $15 billion in national expenditure less the income lost because imports exceeded exports by $8 billion.

In the initial stage, presented in Figure 1, there was a current account surplus and growth in foreign reserves (and of national income) of $10 billion. In the second stage, presented in Figure 2, there was a current account deficit of $8 billion. The net effect over the two stages is a rise in foreign reserves of $2 billion. This net growth in foreign reserves is sufficient relative to the current level of new loans. However, it is sufficient to allow only a small increase in future bank lending.

National income has increased $10 billion in the first stage and by an additional $7 billion in the second stage to grow an additional $17 billion relative to national income at the start.

The transactions that affected the balance sheet of the commercial banks were the loans issued and the purchase of foreign exchange. These can be journalised as:

|

|

|

Debit $ B |

Credit $ B |

|

Loans |

15 |

|

|

|

|

Deposits |

|

15 |

|

Deposits |

8 |

|

|

|

|

Reserve and settlement |

|

8 |

When these are presented in the consolidated balance sheet for the commercial banks, the outcome is as follows:

|

Assets |

$ B |

Liabilities & equity |

$ B |

|

Loans |

3015 |

Deposits |

2517 |

|

Other assets |

850 |

Other liabilities |

600 |

|

Foreign currency reserves |

|

|

|

|

Reserve and settlement |

2 |

|

|

|

Buildings other fixed assets |

150 |

Capital |

900 |

|

Total |

4017 |

Total |

4017 |

The net effect of these transactions is that, under GERLS, deposits have increased $17 billion, loans have increased $15 billion and reserves have increased $2 billion.

For the central bank, the only relevant transaction affecting the balance sheet was the sale of $8 billion in foreign reserves, shown below:

|

|

|

Debit $ B |

Credit $ B |

|

Reserve and settlement |

8 |

|

|

|

|

Foreign currency assets |

|

8 |

When this is included, the central bank’s balance sheet becomes:

|

Assets |

$ B |

Liabilities & equity |

$ B |

|

Foreign currency assets |

1402 |

Currency in circulation |

400 |

|

Local currency assets |

500 |

Foreign currency liabilities |

100 |

|

|

|

Reserve and settlement |

2 |

|

|

|

Other local currency liabilities |

1300 |

|

Buildings other fixed assets |

100 |

Capital |

200 |

|

Total |

2002 |

Total |

2002 |

In this series of transactions using GERLS, there has been a net increase in commercial bank lending of $15 billion. Foreign reserves have increased $2 billion and the net current account surplus was $2 billion. Using GERLS, it is possible to achieve small current account surpluses or a balanced current account.

GERLS offers the central banks a number of levers for guiding the economy. Central banks can influence the exchange rate by determining the guiding exchange rate. Devaluing the guiding exchange rate would stimulate employment and economic growth. Devaluation may have a small inflationary effect as the price of imports would rise.

It should be noted that the exchange rate affects not only relative prices, it also drives the growth of foreign reserves, the growth of bank credit and monetary growth, generally.

Central banks would use the interest rates it pays on deposits in the Reserve and Settlement account to influence the interest rate commercial banks charge on loans and pay on deposits.

Note that because interbank settlements are made using the Reserve and Settlement account, any bank that loses deposits to other banks would suffer falling reserves. Lower reserves would preclude the bank from increasing lending. Therefore, commercial banks must pay competitive interest rates to attract deposits

By influencing interest rates, the central banks also regulate the rate of foreign capital inflow. If the rate of growth of foreign reserves were not sufficient to allow commercial banks to increase their lending, the central bank could raise interest rates. That would attract foreign capital and raise the foreign reserves of the banking system, allowing the commercial banks to increase lending.

The central bank manages the fractional reserve ratio, also. If the central bank sought to increase lending without attracting foreign capital, it could raise the fractional reserve ratio. Alternatively, if there were excessive inflation and the central bank sought to slow monetary growth without attracting foreign capital, it could lower the ratio, increasing the cost of lending for commercial banks.

Inflation would tend to be lower under GERLS than under pure floating exchange rate system because GERLS results in higher rates of economic growth relative to the level of monetary growth.

Prices under the floating exchange rate system tend to increase by the rate of monetary growth divided by the product of the one plus the rate of real economic growth and one plus the rate of growth of bank debt. With GERLS, monetary growth would come from real economic growth from exports so that we would expect the money supply to grow in proportion with income. This would result in low levels of inflation. If the rate of economic growth were equal to the rate of monetary growth, there would be no inflation. If the central bank sought to achieve real economic growth at rate of, say, 10 per cent and inflation of, say, 3 per cent, it would need monetary growth of about 16.7 per cent. Such rules of thumb gained with experience would enable the central bank to monitor and guide the exchange rate to inject money from increased export income into the economy to achieve the economic objectives for which it was established.

For example, to achieve monetary growth of 16.7 per cent per annum, the central bank could regulate the exchange rate and bank lending so as to allow monetary growth of 1.3 per cent per month. If monetary growth were excessive, it could raise the guiding exchange rate to slow the rate of economic growth and the growth of the money supply and reserves. If monetary growth were inadequate, the central bank could lower the guided exchange rate to stimulate export growth and reduce imports, thereby stimulating the domestic economy, raising the rate of growth of the money supply and of foreign reserves.

The Guided Exchange Rate and Liquidity System allows an economy to generate income and increase the money supply in a sustainable manner. It can be used to achieve full employment without causing inflation. It gives central banks the tools it needs to achieve a stable and sustainable monetary system, conducive to economic growth.

Home The impact of the floating exchange rate system on debt Other issues

Mining Investment Boom: A Double Edge Sword for the Australian Economy This article includes an explanation of the optimum exchange rate system. It was first published by Finsia in its inFinance magazine in August 2011.

Last update: 20 December 2015